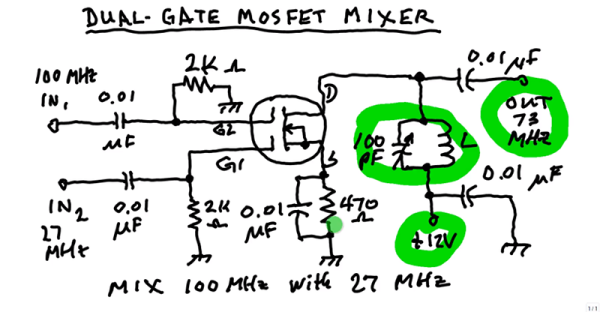

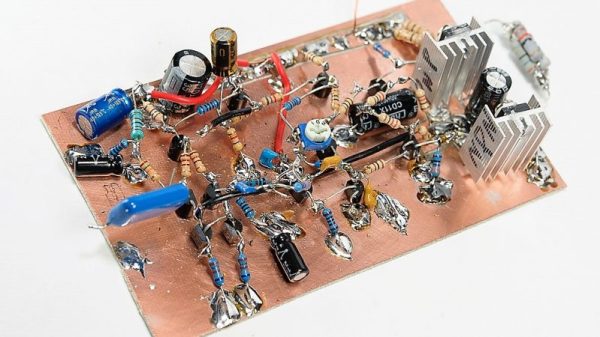

A bandpass allows a certain electrical signal to pass while filtering out undesirable frequencies. In a speaker bandpass, the mid-range speaker doesn’t receive tones meant for the tweeter or woofer. Most of the time, this filtering is done with capacitors to remove low frequencies and inductors to remove high frequencies. In radio, the same concept applies except the frequencies are usually much higher. [The Thought Emporium] is concerned with signals above 300MHz and in this range, a unique type of filter becomes an option. The microstrip filter ignores the typical installation of passive components and uses the copper planes of an unetched circuit board as the elements.

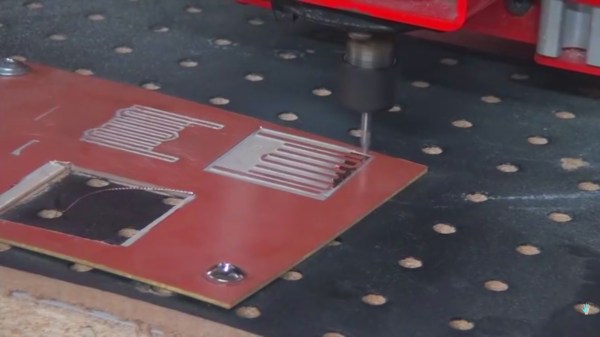

A nice analogy is drawn in the video, which can also be seen after the break, where the copper shapes are compared to the music tuning forks they resemble. The elegance of these filters is their simplicity, repeatability, and reproducability. In the video, they are formed on a CNC mill but any reliable PCB manufacturing process should yield beautiful results. At the size these are made, it would be possible to fit these filters on a business card or a conference badge.