You’ve got to hand it to [Carl Bugeja] — he comes up with some of the most interesting electromechanical designs we’ve seen. His latest project is right up there, too: a single PCB that folds up into a four-wheel motorized rover.

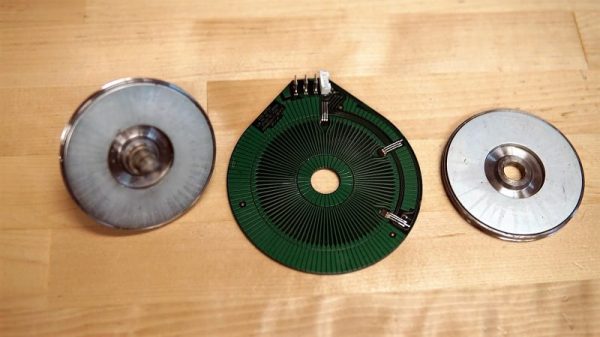

The key to [Carl]’s design lies with his PCB brushless motors, which he has been refining since we first spotted them back in 2018. The idea is to use traces on the PCB for the stator coils to drive a 3D printed rotor containing tiny magnets. They work surprisingly well, even if they don’t generate a huge amount of torque. [Carl]’s flexible PCB design, which incorporates metal stiffeners, is a bit like an unfolded cardboard box, with two pairs of motor coils on each of the side panels. This leaves the other surfaces available for all the electronics, with includes a PIC, a driver chip, and a Hall sensor for each motor, an IMU and proximity sensor for navigation, and an ESP32 to run the show.

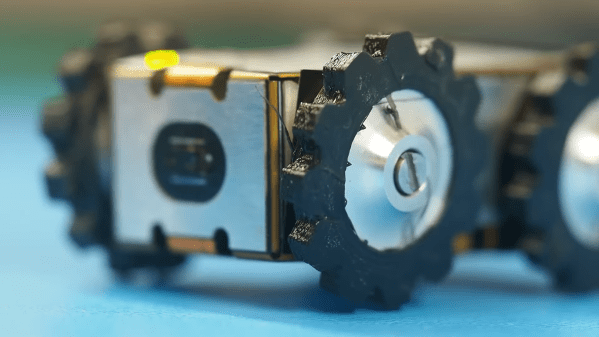

With machined aluminum rotors and TPU tires mounted to the folded-up chassis, it was off to the races, albeit slowly. The lack of torque from the motors and the light weight of the rover, along with some unwanted friction due to ill-fitting joints, added up to slow progress, especially on anything other than a dead flat surface. But with some tweaking, [Carl] was able to get the buggy working well enough to call this one a win. Check out the build and testing in the video below.

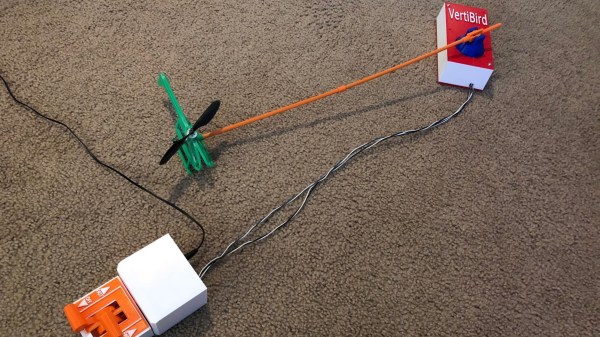

Knowing [Carl], this isn’t the last we’ll see of the foldable rover. After all, he stuck with his two-wheel PCB motor design and eventually got that running pretty well. We’ll be keeping an eye out for progress on this one.

Continue reading “Single Flex PCB Folds Into A Four-Wheel Rover, Complete With Motors”