All computers are vulnerable to attacks by viruses or black hats, but there are lots of steps that can be taken to reduce risk. At the extreme end of the spectrum is having an “air-gapped” computer that doesn’t connect to a network at all, but this isn’t a guarantee that it won’t get attacked. Even transferring files to the computer with a USB drive can be risky under certain circumstances, but thanks to some LED lights that [Robert Fisk] has on his drive, this attack vector can at least be monitored.

Using a USB drive with a single LED that illuminates during a read OR write operation is fairly common, but since it’s possible to transfer malware unknowingly via USB drives, one that has a separate LED specifically for writing operations will help alert a user to any write operations that might be trying to fly under the radar. A recent article by [Bruce Schneier] pointed out this flaw in USB drives, and [Robert] was up to the challenge. His build returns more control to the user by showing them when their drive is accessed and in what way, which can also be used to discover unique quirks of one’s chosen operating system.

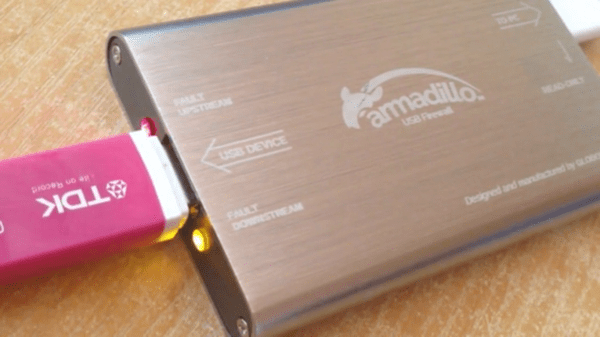

[Robert] is pretty familiar with USB drives and their ups and downs as well. A few years ago he built a USB firewall that was able to decrease the likelihood of BadUSB-type attacks. Be careful going down the rabbit hole of device security, though, or you will start seeing potential attacks hidden almost everywhere.