The epicenter of the Chinese electronics scene drew a lot of attention this week as a 70-story skyscraper started wobbling in exactly the way skyscrapers shouldn’t. The 1,000-ft (305-m) SEG Plaza tower in Shenzhen began its unexpected movements on Tuesday morning, causing a bit of a panic as people ran for their lives. With no earthquakes or severe weather events in the area, there’s no clear cause for the shaking, which was clearly visible from the outside of the building in some of the videos shot by brave souls on the sidewalks below. The preliminary investigation declared the building safe and blamed the shaking on a combination of wind, vibration from a subway line under the building, and a rapid change in outside temperature, all of which we’d suspect would have occurred at some point in the 21-year history of the building. Others are speculating that a Kármán vortex Street, an aerodynamic phenomenon that has been known to catastrophically impact structures before, could be to blame; this seems a bit more likely to us. Regardless, since the first ten floors of SEG Plaza are home to one of the larger electronics markets in Shenzhen, we hope this is resolved quickly and that all our friends there remain safe.

In other architectural news, perched atop Building 54 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology campus in Cambridge for the last 55 years has been a large, fiberglass geodesic sphere, known simply as The Radome. It’s visible from all over campus, and beyond; we used to work in Kendall Square, and the golf-ball-like structure was an important landmark for navigating the complex streets of Cambridge. The Radome was originally used for experiments with weather radar, but fell out of use as the technology it helped invent moved on. That led to plans to remove the iconic structure, which consequently kicked off a “Save the Radome” campaign. The effort is being led by the students and faculty members of the MIT Radio Society, who have put the radome to good use over the years — it currently houses an amateur radio repeater, and the Radio Society uses the dish within it to conduct Earth-Moon-Earth (EME) microwave communications experiments. The students are serious — they applied for and received a $1.6-million grant from Amateur Radio Digital Communications (ARDC) to finance their efforts. The funds will be used to renovate the deteriorating structure.

Well, this looks like fun: Python on a graphing calculator. Texas Instruments has announced that their TI-84 Plus CE Python graphing calculator uses a modified version of CircuitPython. They’ve included seven modules, mostly related to math and time, but also a suite of TI-specific modules that interact with the calculator hardware. The Python version of the calculator doesn’t seem to be for sale in the US yet, although the UK site does have a few “where to buy” entries listed. It’ll be interesting to see the hacks that come from this when these are readily available.

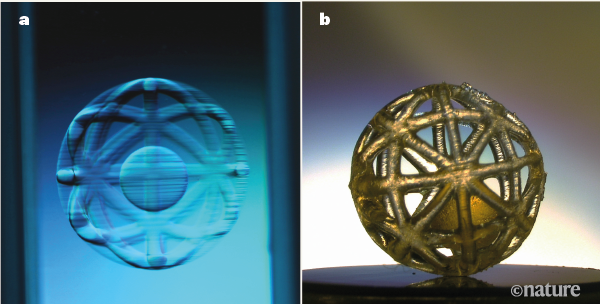

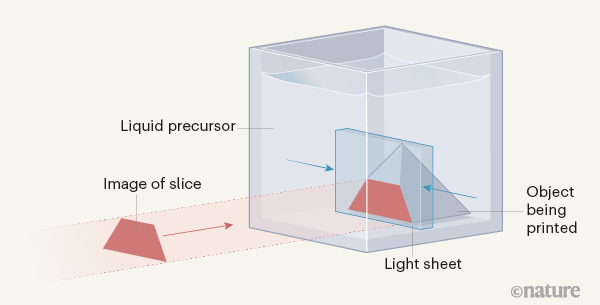

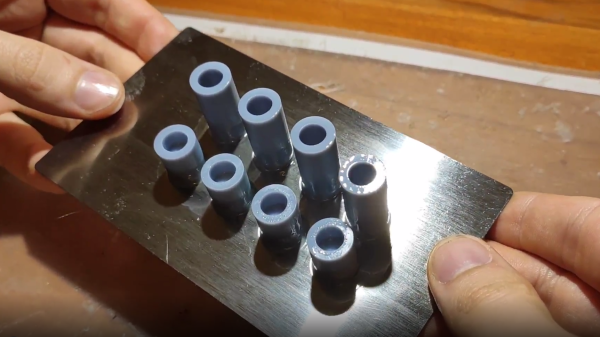

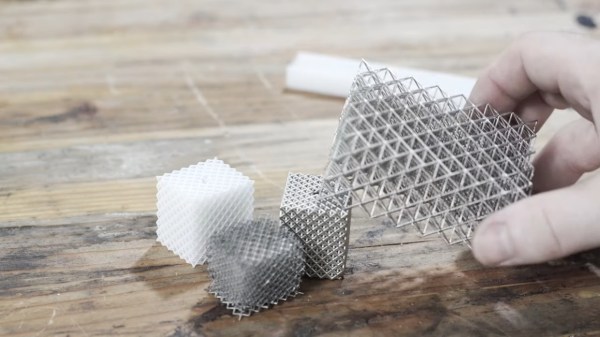

Did you know that PCBWay, the prolific producer of cheap PCBs, also offers 3D-printing services too? We admit that we did not know that, and were therefore doubly surprised to learn that they also offer SLA resin printing. But what’s really surprising is the quality of their clear resin prints, at least the ones shown on this Twitter thread. As one commenter noted, these look more like machined acrylic than resin prints. Digging deeper into PCBWay’s offerings, which not only includes all kinds of 3D printing but CNC machining, sheet metal fabrication, and even injection molding services, it’s becoming harder and harder to justify keeping those capabilities in-house, even for the home gamer. Although with what we’ve learned about supply chain fragility over the last year, we don’t want to give up the ability to make parts locally just yet.

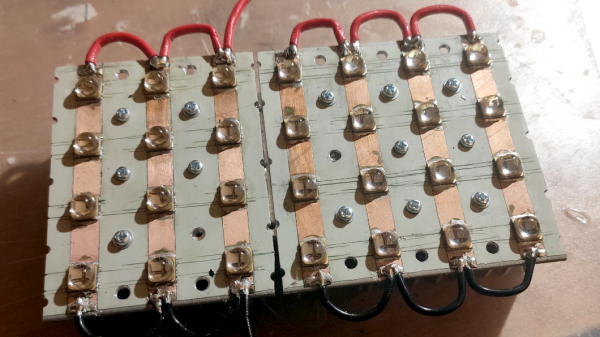

And finally, how well-calibrated are your fingers? If they’re just right, perhaps you can put them to use for quick and dirty RF power measurements. And this is really quick and really dirty, as well as potentially really painful. It comes by way of amateur radio operator VK3YE, who simply uses a resistive dummy load connected to a transmitter and his fingers to monitor the heat generated while keying up the radio. He times how long it takes to not be able to tolerate the pain anymore, plots that against the power used, and comes up with a rough calibration curve that lets him measure the output of an unknown signal. It’s brilliantly janky, but given some of the burns we’ve suffered accidentally while pursuing this hobby, we’d just as soon find another way to measure RF power.