It may be hard to believe, but it’s time for the Hackaday Prize again! The 2023 Hackaday Prize was announced last weekend at Hackaday Berlin, and entries are already pouring in. The first-round challenge is all about “Re-engineering Education,” which means you’ve got to come up with a project idea that helps push back the veil of ignorance somehow. Perhaps you’ve got a novel teaching tool in mind, or a way to help students learn remotely. Or maybe your project is aimed at getting students involved and engaged. Whatever it is — and whatever the subject matter; it doesn’t just have to be hacking-adjacent — get an entry together, build a team, and get to work. The first round closes on April 25, so get to it!

Author: Dan Maloney3373 Articles

Modern Dance Or Full-Body Keyboard? Why Not Both!

If you felt in your heart that Hackaday was a place that would forever be free from projects that require extensive choreography to pull off, we’re sorry to disappoint you. Because you’re going to need a level of coordination and gross motor skills that most of us probably lack if you’re going to type with this full-body, semaphore-powered keyboard.

This is another one of [Fletcher Heisler]’s alternative inputs projects, in the vein of his face-operated coding keyboard. The idea there was to be able to code with facial gestures while cradling a sleeping baby; this project is quite a bit more expressive. Pretty much all you need to know about the technical side of the project can be gleaned from the brilliant “Hello world!” segment at the start of the video below. [Fletcher] uses OpenCV and MediaPipe’s Pose library for pose estimation to decode the classic flag semaphore alphabet, which encodes characters in the angle of the signaler’s extended arms relative to their body. To extend the character set, [Fletcher] added a squat gesture for numbers, and a shift function controlled by opening and closing the hands. The jazz-hands thing is just a bonus.

Honestly, the hack here is mostly a brain hack — learning a complex series of gestures and stringing them together fluidly isn’t easy. [Fletcher] used a few earworms to help him master the character set and tune his code; the inevitable Rickroll was quite artistic, and watching him nail the [Johnny Cash] song was strangely satisfying. We also thoroughly enjoyed the group number at the end. Ooga chaka FTW.

Continue reading “Modern Dance Or Full-Body Keyboard? Why Not Both!”

See Satellites In Broad Daylight With This Sky-Mapping Dish Antenna

If you look up at the night sky in a dark enough place, with enough patience you’re almost sure to see a satellite cross the sky. It’s pretty cool to think you’re watching light reflect off a hunk of metal zipping around the Earth fast enough to never hit it. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work during the daylight hours, and you really only get to see satellites in low orbits.

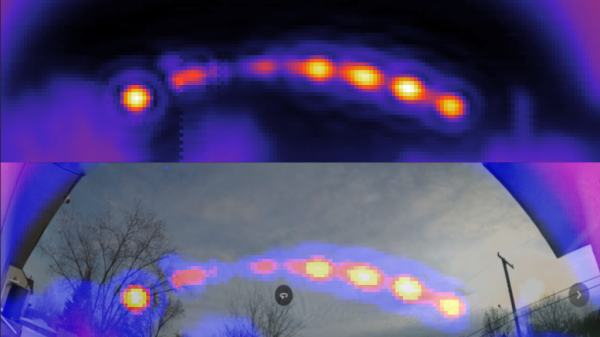

Thankfully, there’s a trick that allows you to see satellites any time of day, even the ones in geosynchronous orbits — you just need to look using microwaves. That’s what [Gabe] at [saveitforparts] did with a repurposed portable satellite dish, the kind that people who really don’t like being without their satellite TV programming when they’re away from home buy and quickly sell when they realize that toting a satellite dish around is both expensive and embarrassing. They can be had for a song, and contain pretty much everything needed for satellite comms in one package: a small dish on a motorized altazimuth mount, a low-noise block amplifier (LNB), and a single-board computer that exposes a Linux shell.

After figuring out how to command the dish to specific coordinates and read the signal strength of the received transponder signals, [Gabe] was able to cobble together a Python program to automate the task. The data from these sweeps of the sky resulted in heat maps that showed a clear arc of geosynchronous satellites across the southern sky. It’s quite similar to something that [Justin] from Thought Emporium did a while back, albeit in a much more compact and portable package. The video below has full details.

[Gabe] also tried turning the dish away from the satellites and seeing what his house looks like bathed in microwaves reflected from the satellite constellation, which worked surprisingly well — well enough that we’ll be trawling the secondary market for one of these dishes; they look like a ton of fun.

Continue reading “See Satellites In Broad Daylight With This Sky-Mapping Dish Antenna”

Hackaday Podcast 212: Staring Through ICs, Reading Bloom Filters, And Repairing, Reworking, And Reballing

It was quite the cornucopia of goodness this week as Elliot and Dan sat down to hash over the week in hardware hacking. We started with the exciting news that the Hackaday Prize is back — already? — for the tenth year running! The first round, Re-Engineering Education, is underway now, and we’re already seeing some cool entries come in. The Prize was announced at Hackday Berlin, about which Elliot waxed a bit too. Speaking of wax, if you’re looking to waterproof your circuits, that’s just one of many coatings you might try. If you’re diagnosing a problem with a chip, a cheap camera can give your microscope IR vision. Then again, you might just use your Mark I peepers to decode a ROM. Is your FDM filament on the wrong spool? We’ve got an all-mechanical solution for that. We’ll talk about tools of the camera operator’s trade, the right to repair in Europe, Korean-style toasty toes, BGA basics, and learn just what the heck a bloom filter is — or is it a Bloom filter?

Check out the links below if you want to follow along, and as always, tell us what you think about this episode in the comments!

Download your own personal copy!

Stripped Clock Wheel Gets A New Set Of Teeth, The Hard Way

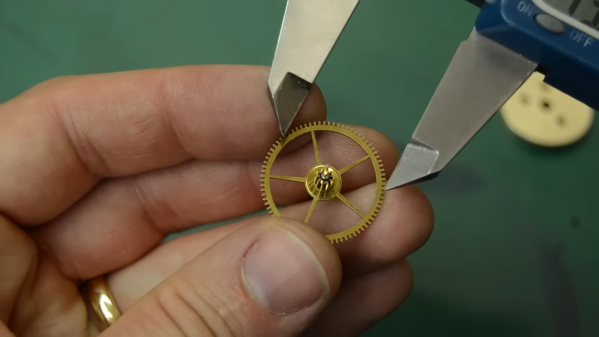

If there’s one thing we’ve learned from [Chris] at Clickspring, it’s that a clockmaker will stop at nothing to make a clock not only work perfectly, but look good doing it. That includes measures as extreme as this complete re-toothing of a wheel from a clock. Is re-toothing even a word?

The obsessive horologist in this case is [Tommy Jobson], who came across a clock that suffered a catastrophic injury: a sudden release of energy from the fusee, the cone-shaped pulley that adjusts for the uneven torque created by the clock’s mainspring. The mishap briefly turned the movement into a lathe that cut the tops off all the teeth on the main wheel.

Rather than fabricate a completely new wheel, [Tommy] chose to rework the damaged one. After building a special arbor to hold the wheel, he turned it down on the lathe, leaving just the crossings and a narrow rim. A replacement blank was fabricated from brass and soldered to the toothless wheel, turned to size, and given a new set of teeth using one of the oddest lathe setups we’ve ever seen. Once polished and primped, the repair is only barely visible.

Honestly, the repaired wheel looks brand new to us, and the process of getting it to that state was fascinating to watch. If the video below whets your appetite for clockmaking, have we got a treat for you.

Continue reading “Stripped Clock Wheel Gets A New Set Of Teeth, The Hard Way”

Two-Tube Spy Transmitter Fits In The Palm Of Your Hand

It’s been a long time since vacuum tubes were cutting-edge technology, but that doesn’t mean they don’t show up around here once in a while. And when they do, we like to feature them, because there’s still something charming, nay, romantic about a circuit built around hot glass and metal. To wit, we present this compact two-tube “spy radio” transmitter.

From the look around his shack — which we love, by the way — [Helge Fykse (LA6NCA)] really has a thing for old technology. The typewriter, the rotary phones, the boat-anchor receiver — they all contribute to the retro feel of the space, as well as the circuit he’s working on. The transmitter’s design is about as simple as can be: one tube serves as a crystal-controlled oscillator, while the other tube acts as a power amplifier to boost the output. The tiny transmitter is built into a small metal box, which is stuffed with the resistors, capacitors, and homebrew inductors needed to complete the circuit. Almost every component used has a vintage look; we especially love those color-coded mica caps. Aside from PCB backplane, the only real nod to modernity in the build is the use of 3D printed forms for the coils.

But does it work? Of course it does! The video below shows [Helge] making a contact on the 80-meter band over a distance of 200 or so kilometers with just over a watt of power. The whole project is an excellent demonstration of just how simple radio communications can be, as well as how continuous wave (CW) modulation really optimizes QRP setups like this.

Continue reading “Two-Tube Spy Transmitter Fits In The Palm Of Your Hand”

Kino Wheels Gives You A Hand Learning Camera Operation

Have you ever watched a movie or a video and really noticed the quality of the camera work? If you have, chances are the camera operator wasn’t very skilled, since the whole point of the job is to not be noticed. And getting to that point requires a lot of practice, especially since the handwheel controls for professional cameras can be a little tricky to master.

Getting the hang of camera controls is the idea behind [Cadrage]’s Kino Wheels open-source handwheels. The business end of Kino Wheels is a pair of DIN 950 140mm spoked handwheels — because of course there’s a DIN standard for handwheels. The handwheels are supported by sturdy pillow block bearings and attached to 600 pulse/rev rotary encoders, which are read by an Arduino Mega 2560. The handwheels are mounted orthogonal to each other in a suitable enclosure; the Pelican-style case shown in the build instructions seems like a perfect choice, but it really could be just about anything.

To use Kino Wheels, [Cadrage] offers a free camera simulator for Windows. Connected over USB, the wheels control the pan and tilt axes of a simulated camera in an animated scene. The operator-in-training uses the wheels to keep the scene composed properly while following the action. A little bit of the simulation is shown in the brief video below, along with some of the build details.

While getting camera practice is the point of the project, that’s not to say Kino Wheels couldn’t be retasked. With a little work, these could be used to actually control at least a couple of axes of a motion control rig, or maybe even to play Quake.

Continue reading “Kino Wheels Gives You A Hand Learning Camera Operation”