To get its engineers thinking about design for assembly back in the 1980s, Westinghouse made a video about a product optimized for assembly: the IBM Proprinter. The technology may be dated, but the film presents a great look at how companies designed not only for manufacturing, but also for ease of assembly.

It’s not clear whether Westinghouse and IBM collaborated on the project, but given the inside knowledge of the dot-matrix printer’s assembly, it seems like they did. The first few minutes are occupied by an unidentified Westinghouse executive talking about design for assembly in general terms, and how it impacts the bottom line. Skip ahead to 3:41 if talking suits aren’t your thing.

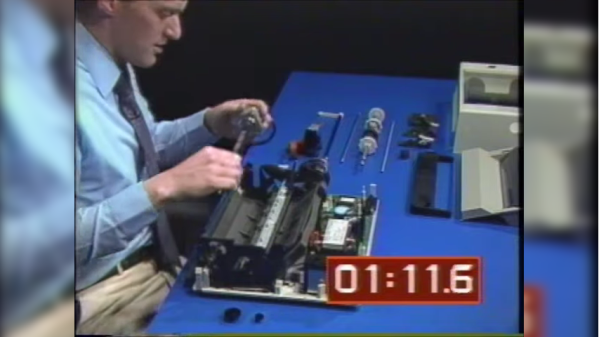

Once the engineer gets going on the printer, though, things get really interesting. The printer’s guts are laid out before him, ready to be assembled. What’s notably absent from the table are tools — the Proprinter was so well designed that the only tool needed is a pair of human hands. And they don’t have to be particularly dexterous hands, either — the design favors motions that are straight down, letting gravity assist the assembly process and preventing assemblers from the need to contort their bodies. Almost everything is held in place by compliant mechanisms built into the plastic parts. There are a few gems in the film, like the plastic lead screw that drives the printhead, obviating the need to string a fussy timing belt, or the unique roller that twists to lock onto a long shaft, rather than having to be pushed to its center.

We found this film which we’ve placed below the break to be very instructive, and the fact that a device as complex as a printer can be assembled in just a few minutes without picking up a single tool is pretty illustrative of the power of designing for assembly. Slick designs that can’t be manufactured at scale are all too common in this age of powerful design tools and desktop manufacturing, so these lessons from the past might be worth relearning.

Continue reading “Retrotechtacular: Design For Assembly, 1980s-Style”