[Mirko Pavleski] has put together a little weather station for himself that combines Internet-sourced forecasts with physical sensor data to give him a complete view of his local conditions. There’s no shortage of weather applications for our smartphones and computers that will show us the current local conditions and the forecast for the next couple of days. It’s so easy to pull weather data from the various APIs out there that you even see the functionality “baked in” to different gadgets these days. Of course, you can dig through every weather API in the world and not find the temperature and humidity inside your office; for that, you need your own sensors.

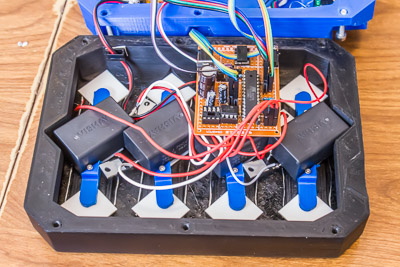

[Mirko] took a somewhat unconventional approach by essentially building two totally separate weather devices and packing them into one enclosure, which gives the final device a rather unique look thanks to the contrasting display technologies used.

Local conditions are detected by an Arduino Nano connected to a BMP180 sensor and displayed on a Nokia 5110 LCD. The screen shows not only real-time temperature and barometric pressure, but the change in pressure over the last several hours. The three-day forecast, on the other hand, is provided by a NodeMCU ESP8266 development board connected to the increasingly ubiquitous 0.96 inch OLED.

If you’re not into the whole duality thing and would rather do it all on the same device, you might be interested in one of the ESP8266 weather monitors we’ve seen in the past.