The 555 timer is one of the most versatile integrated circuits available. It can generate PWM signals, tones, and single-shot pulses. You can even put one in a bi-stable mode similar to a flip flop. All of these modes are available by only changing a few components outside of the IC itself. It’s also dirt cheap, so it finds its way into all kinds of applications its original inventors never imagined. There’s a bit of a trope around here as well that you ought not to use a microcontroller when one of these will do, and while it’s a bit of a played-out comment, it’s often more true than it seems. This video shows a few uncommon ways of using these circuits instead of putting a microcontroller to work.

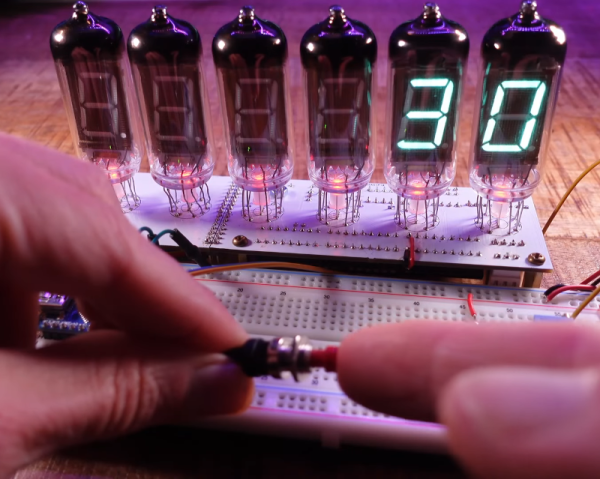

After a brief overview of the internals of the hallowed 555, [Doctor Volt] walks us through some of its uses, starting with applications for digital inputs, including a debounce circuit and a toggle switch. From there, he moves on to demonstrating a circuit that can protect batteries from deep discharge, and a small change to that circuit can turn the 555 into a resetting fuse that can protect against short circuit events. Finally, the PWM capabilities of this small integrated circuit are put to work as an audio amplifier, although perhaps not one that would pass muster for the most devout audiophiles among us.

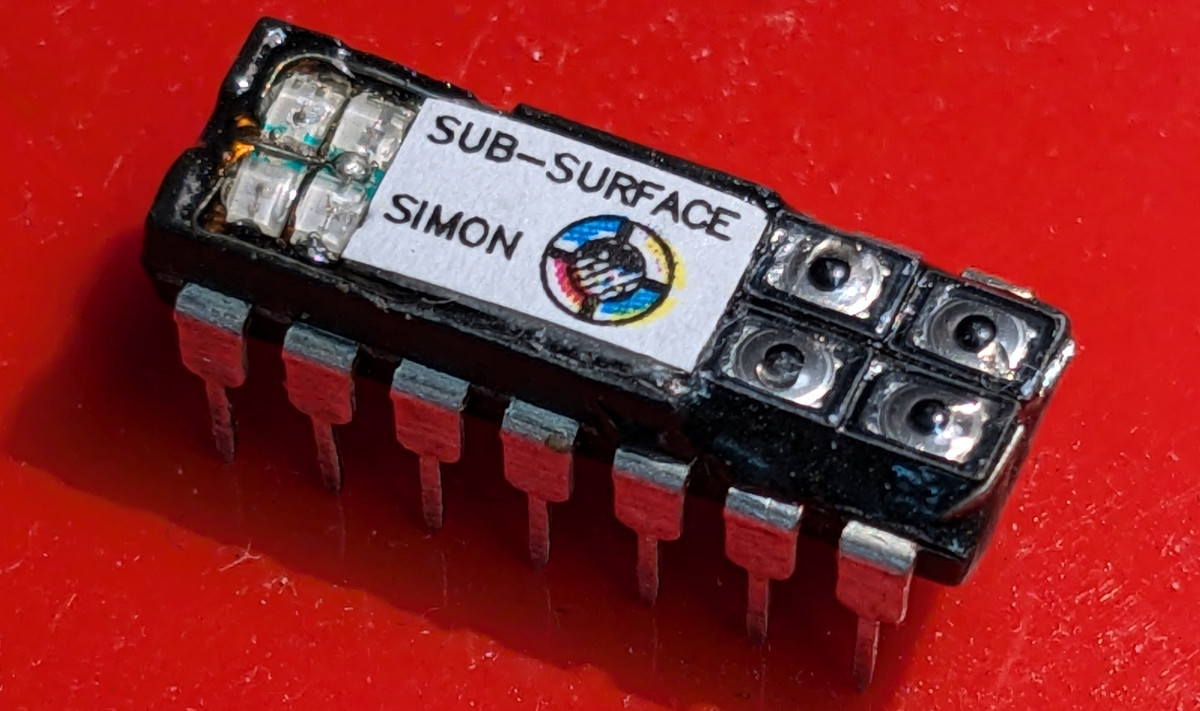

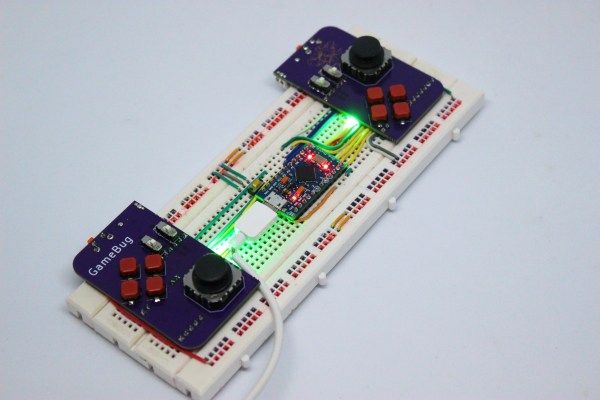

Even though it’s possible to offload a lot of the capabilities of a 555 onto a microcontroller, there’s certainly an opportunity to offload some things to the 555, even if your project still needs a microcontroller. However, offloading tasks like debounce or input latching to hardware rather than spending microcontroller cycles or pins can make a project more robust, both from reliability and software points of view. For some other useful circuits, some of which have been forgotten in the modern microcontroller age, it’s worth taking a look at some of these antique circuit books as well. While we are sure the 555 designers hoped it would be a big hit, no one imagined this giant one.