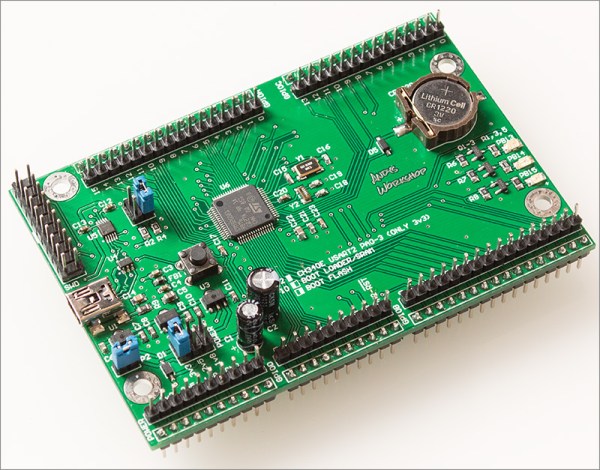

Electric motors are easy to make; remember those experiments with wire-wrapped nails? But what’s easy to make is often hard to engineer, and making a motor that’s small, light, and powerful can be difficult. [Carl Bugeja] however is not one to back down from a challenge, and his tiny “jigsaw” PCB motor is the latest result of his motor-building experiments.

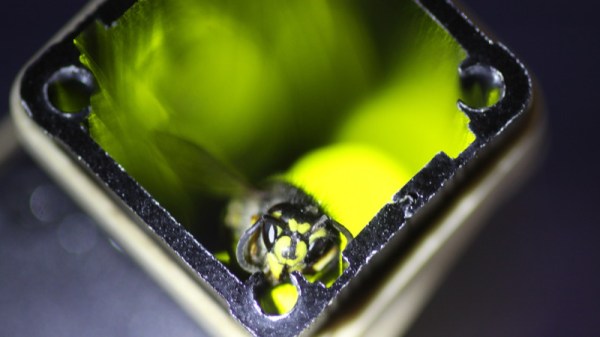

We’re used to seeing brushless PCB motors from [Carl], but mainly of the axial-flux variety, wherein the stator coils are arranged so their magnetic lines of force are parallel to the motor’s shaft – his tiny PCB motors are a great example of this geometry. While those can be completely printed, they’re far from optimal. So, [Carl] started looking at ways to make a radial-flux PCB motor. His design has six six-layer PCB coils soldered perpendicular to a hexagonal end plate. The end plate has traces to connect the coils in a star configuration, and together with a matching top plate, they provide support for tiny bearings. The rotor meanwhile is a 3D-printed cube with press-fit neodymium magnets. Check out the build in the video below.

Connected to an ESC, the motor works decently, but not spectacularly. [Carl] admits that more tweaking is in order, and we have little doubt he’ll keep optimizing the design. We like the look of this, and we’re keen to see it improved.

Continue reading “Jigsaw Motor Uses PCB Coils For Radial Flux”