Having a child is perhaps the greatest “hack” a human can perform. There’s no soldering iron, no Arduino (we hope), but in the end, you’ve managed to help create the most complex piece of machinery in the known galaxy. The joys of having a child are of course not lost on the geekier of our citizens, for they wonder the same things that all new parents do: how do we make sure the baby is comfortable, how many IR LEDs do we need to see her in the dark, and of course the age old question, should we do this with a web app or go native?

If you’re the kind of person who was frustrated to see that “What to Expect When You’re Expecting” didn’t even bother to mention streaming video codecs, then you’ll love FruitNanny, the wonderfully over-engineered baby monitor created by [Dmitry Ivanov]. The product of nearly two years of development, FruitNanny started as little more than a Raspberry Pi 1n a plastic lunch box. But as [Dmitry] details in his extensive write-up, the latest iteration could easily go head-to-head with products on the commercial market.

If you’re the kind of person who was frustrated to see that “What to Expect When You’re Expecting” didn’t even bother to mention streaming video codecs, then you’ll love FruitNanny, the wonderfully over-engineered baby monitor created by [Dmitry Ivanov]. The product of nearly two years of development, FruitNanny started as little more than a Raspberry Pi 1n a plastic lunch box. But as [Dmitry] details in his extensive write-up, the latest iteration could easily go head-to-head with products on the commercial market.

[Dmitry] gives a full bill of materials on his page, but all the usual suspects are here. A Raspberry Pi 3 paired with the official NoIR camera make up the heart of the system, and the extremely popular DHT22 handles the environmental monitoring. A very nice 3D printed case, a lens intended for the iPhone, and a dozen IR LEDs round out the build.

The software side is where the project really kicks into high gear. Reading through the setup instructions [Dmitry] has provided is basically a crash course in platform-agnostic video streaming. Even if a little bundle of joy isn’t on your development roadmap, there’s probably a tip or two you can pick up for your next project that requires remote monitoring.

It probably won’t surprise you that geeky parents have been coming up with ways to spy on their kids for some time now, and if you can believe it, some don’t even include a Raspberry Pi.

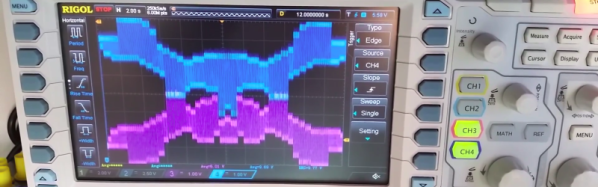

On paper, a light bulb lights up when you put current through it. In real life, it is a bit more complicated. An incandescent filament starts off as almost a dead short and draws a lot of current for a very brief time. As the current flows, the filament gets hot and the resistance goes up. That reduces the current draw. This effect — known as inrush current — is the scourge of designers trying to turn on light bulbs with transistors or other electronic switches.

On paper, a light bulb lights up when you put current through it. In real life, it is a bit more complicated. An incandescent filament starts off as almost a dead short and draws a lot of current for a very brief time. As the current flows, the filament gets hot and the resistance goes up. That reduces the current draw. This effect — known as inrush current — is the scourge of designers trying to turn on light bulbs with transistors or other electronic switches.