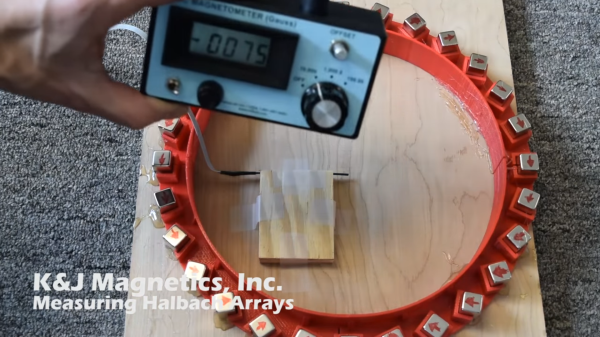

[Klaus Halbach] gets his name attached to these clever arrangements of permanent magnets but the effect was discovered by [John C. Mallinson]. Mallinson array sounds good too, but what’s in a name? A Halbach array consists of permanent magnets with their poles rotated relative to each other. Depending on how they’re rotated, you can create some useful patterns in the overall magnetic field.

Over at the K&J Magnetics blog, they dig into the effects and power of these arrays in the linear form and the circular form. The Halbach effect may not be a common topic over dinner, but the arrays are appearing in some of the best tech including maglev trains, hoverboards (that don’t ride on rubber wheels), and the particle accelerators they were designed for.

Once aligned, these arrays sculpt a magnetic field. The field can be one-sided, neutralized at one point, and metal filings are used to demonstrate the shape of these fields in a quick video. In the video after the break, a powerful magnetic field is built but when a rare earth magnet is placed in the center, rather than blasting into one of the nearby magnets, it wobbles lazily.

Be careful when working with powerful magnets, they can pinch and crush, but go ahead and build your own levitating flyer or if you came for hoverboards, check out this hoverboard built with gardening tools.

A can of soda costs about half a dollar, and once you’re done with the sugary syrup, most cans end up in the trash headed for recycling. Some folks re-use them for other purposes, but we’re guessing no one up-cycles them quite like artist [Noah Deledda] does. He turns them into pieces of

A can of soda costs about half a dollar, and once you’re done with the sugary syrup, most cans end up in the trash headed for recycling. Some folks re-use them for other purposes, but we’re guessing no one up-cycles them quite like artist [Noah Deledda] does. He turns them into pieces of