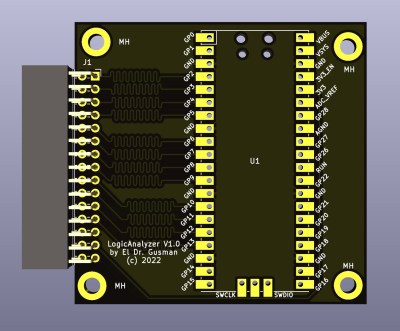

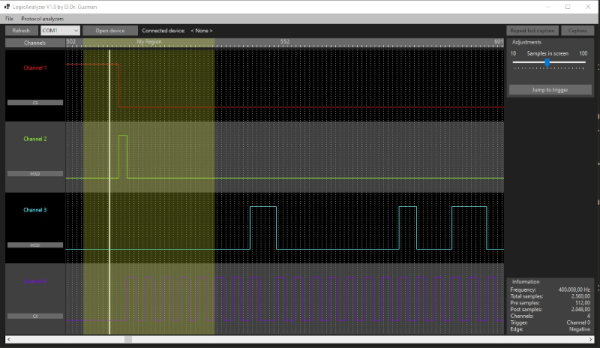

A common enough microcontroller project is to create some form of logic analyzer. In theory, it should be pretty easy: grab some digital inputs, store them, and display them. But, of course, the devil is in the details. First, you want to grab data fast, but you also need to examine the trigger in real time — hard to do in software. You may also need input conditioning circuitry unless you are satisfied with the microcontroller’s input characteristics. Finally, you need a way to dump the data for analysis. [Gusmanb] has tackled all of these problems with a simple analyzer built around the Raspberry Pi Pico.

On the front and back ends, there is an optional board that does fast level conversion. If you don’t mind measuring 3.3 V inputs, you can forego the board. On the output side, there is custom software for displaying the results. What’s really interesting, though, is what is in between.

The Pico grabs 24 bits of data at 100 MHz and provides edge and pattern triggers. This is impressive because you need to look at the data as you store it and that eats up a few instruction cycles if you try to do it in software, dropping your maximum clock rate. So how does this project manage it?

It uses the Pico’s PIO units are auxiliary dedicated processors that aren’t very powerful, but they are very fast and deterministic. Two PIO instructions are enough to handle the work for simple cases. However, there are two PIOs and each has four separate state machines. It still takes some work, but it is easier than trying to run a CPU at a few gigahertz to get the same effect. The fast trigger mode, in particular, abuses the PIO to get maximum speed and can even work up to 200 MHz with some limitations.

If you want to try it, you can use nothing more than a Pico and a jumper wire as long as you don’t need the level conversion. The project page mentions that custom software avoids using OpenBench software, which we get, but we might have gone for Sigrok drivers to prevent having to reinvent too many wheels. The author mentions that it was easier to roll your own code than conform to a driver protocol and we get that, too. Still, the software looks nice and even has an SPI protocol analyzer. It is all open source, so if you want other protocols before the author gets to them, you could always do it yourself.

If you do want a Pico and Sigrok, we’ve covered a project that does just that. Most of the logic analyzers we use these days we build into our FPGA designs.

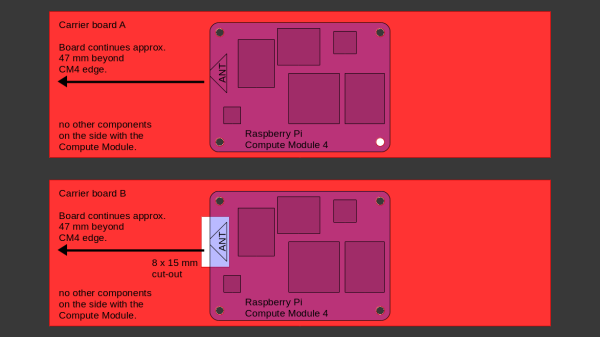

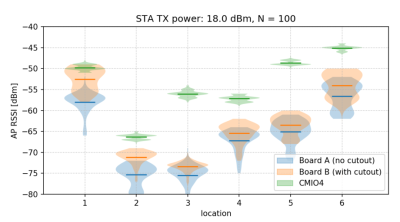

After setting up some test locations and writing a few scripts for ease of testing, [Avian] recorded the experiment data. Having that data plotted, it would seem that, while presence of an under-antenna cutout helps, it doesn’t affect RSSI as much as the module placement does. Of course, there’s way more variables that could affect RSSI results for your own designs – thankfully, the scripts used for logging are available, so you can test your own setups if need be.

After setting up some test locations and writing a few scripts for ease of testing, [Avian] recorded the experiment data. Having that data plotted, it would seem that, while presence of an under-antenna cutout helps, it doesn’t affect RSSI as much as the module placement does. Of course, there’s way more variables that could affect RSSI results for your own designs – thankfully, the scripts used for logging are available, so you can test your own setups if need be.

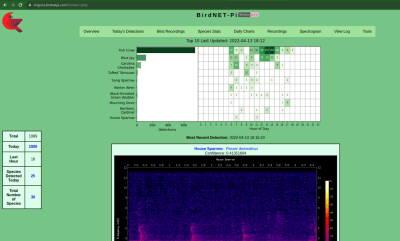

About that Raspberry Pi version! There’s a sister project called

About that Raspberry Pi version! There’s a sister project called