Unless you happen to be a retro enthusiast, it’s fair to say that any photography you do (whether on your phone or a dedicated camera) is going to be digital. The world of photography has all but completely moved away from film, but the transition was not instantaneous. Instead there was a period of about ten years from the mid-90s when film and digital existed side-by-side in some form. A profitable sideline for photography shops was providing scans of film, and there were a series of high-end scanners aimed at that market.

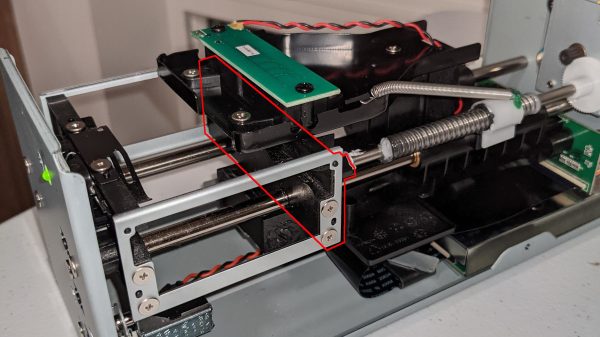

[Kai Kaufman] shares the experience of making one of these work with a modern Windows version, and it’s interesting both because of the scanner itself and the epic tale of software detective work required to bring it up to date. The scanner in question is a Pakon F135, the product of a Kodak acquisition, and an all-in-one device that simply spools in a roll of film and does all the hard work of identifying the frames, cropping the images, and reading any other data from the film.

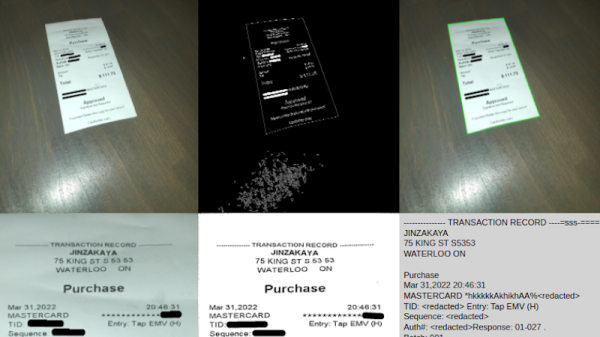

You may never have seen one of these machines, but if you ever had your photos on a CD as well as printed back in the day you’ve probably had its output. The problem in 2022 is that these machines have drivers which only work with relatively ancient 32-bit Windows versions, so most of the write-up involves some significant detective work into the drivers.

Not every reader will be an expert on Windows driver de-compilation, but perhaps the most interesting pieces of the puzzle come from his detective work in finding the origin of some components. Example code from Microsoft and from a chip design company both make the job much easier, and the final result is a fully functioning 64-bit driver for the device. Not many people will have a Pakon film scanner, but for those who do it seems life may just have become a bit easier.

Thanks [adilosa] for the tip!

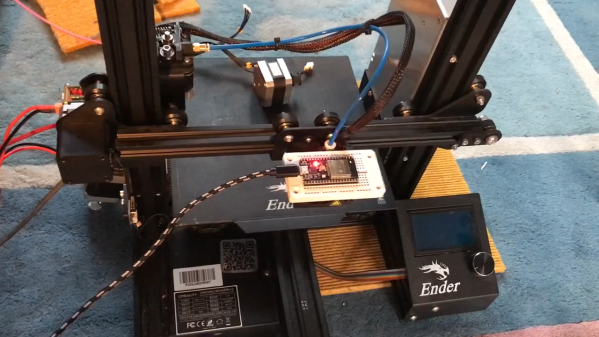

Granted, based as it is on the gantry of an old 3D printer, [Neumi]’s WiFi scanner has a somewhat limited work envelope. A NodeMCU ESP32 module rides where the printer’s extruder normally resides, and scans through a series of points one centimeter apart. A received signal strength indicator (RSSI) reading is taken from the NodeMCU’s WiFi at each point, and the position and RSSI data for each point are saved to a CSV file. A couple of Python programs then digest the raw data to produce both 2D and 3D scans. The 3D scans are the most revealing — you can actually see a 12.5-cm spacing of signal strength, which corresponds to the wavelength of 2.4-GHz WiFi. The video below shows the data capture process and some of the visualizations.

Granted, based as it is on the gantry of an old 3D printer, [Neumi]’s WiFi scanner has a somewhat limited work envelope. A NodeMCU ESP32 module rides where the printer’s extruder normally resides, and scans through a series of points one centimeter apart. A received signal strength indicator (RSSI) reading is taken from the NodeMCU’s WiFi at each point, and the position and RSSI data for each point are saved to a CSV file. A couple of Python programs then digest the raw data to produce both 2D and 3D scans. The 3D scans are the most revealing — you can actually see a 12.5-cm spacing of signal strength, which corresponds to the wavelength of 2.4-GHz WiFi. The video below shows the data capture process and some of the visualizations.