It’s amazing when a skilled hacker reverse-engineers a proprietary format and shares the nitty-gritty with everyone. Today is a day when we get one such write-up – about MemoryStick. It is one of those proprietary formats, a staple of Sony equipment, these SD-card-like storage devices were evidently designed to help pad Sony’s pockets, as we can see from the tight lock-in and inflated prices. As such, this format has always remained unapproachable to hackers. No more – [Dmitry Grinberg] is here with an extensive breakdown of MemoryStick protocol and internals.

If you ever want to read about a protocol that is not exactly sanely designed, from physical layer quirks to things like inexplicable large differences between MemoryStick and MemoryStick Pro, this will be an entertaining read for hackers of all calibers. Dmitry doesn’t just describe the bad parts of the design, however, as much as that rant is entertaining to read – most of the page is taken by register summaries, struct descriptions and insights, the substance about MemoryStick that we never got.

One sentence is taken to link to a related side project of [Dmitry] that’s a rabbithole on its own – he has binary patched MemoryStick drivers for PalmOS to add MemoryStick Pro support to some of the Sony Clie handhelds. Given the aforementioned differences between non-Pro and Pro standards, it’s a monumental undertaking for a device older than some of this site’s readers, and we can’t help but be impressed.

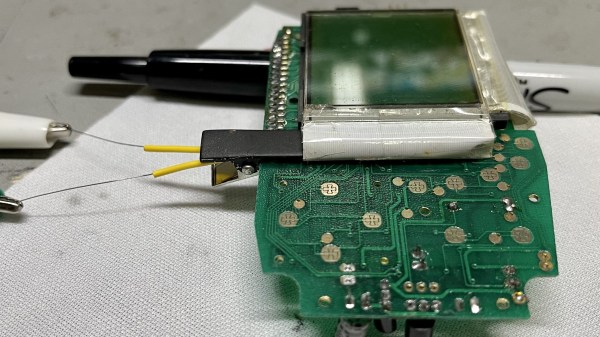

To finish the write-up off, [Dmitry] shares with us some MemoryStick bit-banging examples for the STM32. Anyone who ever wanted to approach MemoryStick, be it for making converter adapters to revive old tech, data recovery or preservation purposes, or simply hacker curiosity, now can feel a bit less alone in their efforts.

We are glad to see such great hacking on the MemoryStick front – it’s much needed, to the point where our only article mentioning MemoryStick is about avoiding use of the MemoryStick slot altogether. [Dmitry] is just the right person for reverse-engineering jobs like this, with extensive reverse-engineering history we’ve been keeping track of – his recent reverse-engineering journey of an unknown microcontroller in cheap E-Ink devices is to behold.