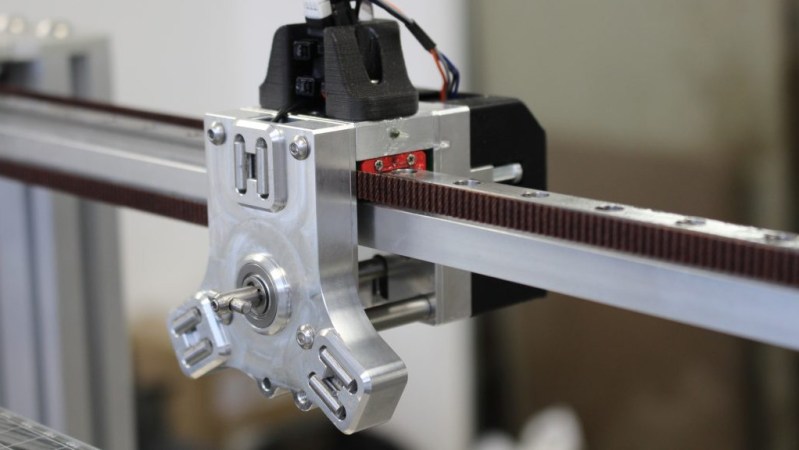

Want a closer, in-depth look at E3D’s motion system and tool-changing platform? [Kubi Sertoglu] shared his impressions after building and testing the system, which comes in the form of a parts bundle direct from E3D costing just under $3000 USD. The project took [Kubi] about 15 hours and is essentially built from the ground up. The system is definitely aimed at engineers and advanced prosumers, but [Kubi] found it to be of remarkable quality, and is highly pleased with the end results.

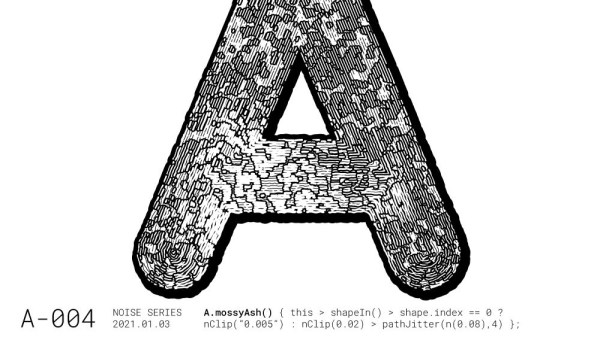

We first saw E3D’s design announced back in 2018, when they showed their working ideas for a system that combined motion control and a toolchanger design. The system [Kubi] built uses four 3D printing extruders for multi-material prints, but in theory the toolheads could just as easily be things like grippers, lasers, or engravers instead of 3D printing extruders.

One challenge with tool changing is ensuring tools mount and locate back into the same place, time after time. After all, a few fractions of a millimeter difference in the position of a print head would spell disaster for the quality of most prints. Kinematic couplings are the answer to being sure something goes back where it should, but knowing the solution is only half the battle. Implementation still requires plenty of clever design and hard engineering work, which is what E3D has delivered.

Want a closer look at the nitty-gritty? Check out E3D’s GitHub repository for all the details on their toolchanger and motion system.