In 1976, Texas Instruments came out with the TL084, a four JFET op-amp IC each with similar circuitry to Fairchild’s very popular single op-amp 741. But even though the 741 has been covered in detailed, when [Ken Shirriff] focused his microscope on a TL084, he found some very interesting things.

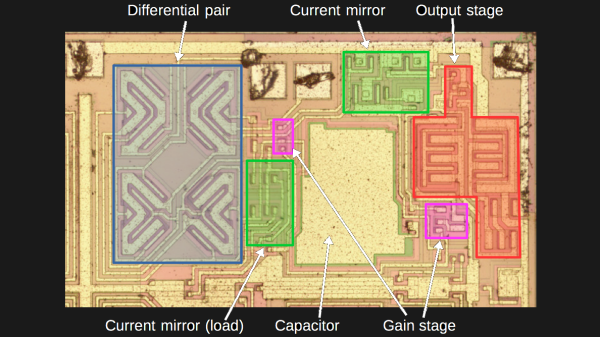

To avoid using acid to get at the die, he instead found a ceramic packaged TL084 and pried off the cover. The first things he saw were four stabilizing capacitors, by far the largest structures on the die and visible to the naked eye.

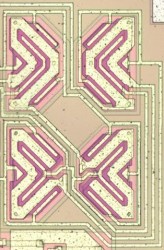

When he peered into his microscope he next saw butterfly shapes which turned out to be pairs of input JFETs. The wide strips are the gates and the narrower strip surrounded by each gate is the source. The drain is the narrow strip surrounding each gate. Why arrange four JFETs like this? It’s possible to have temperature gradients in the IC, one side being hotter than the other. These gradients can affect the JFET’s characteristics, unbalancing the inputs. Look closely at the way the JFETs are connected and you’ll see that the top-left one is connected to the bottom-right one, and similarly for the other two. This diagonal cross-connecting cancels out any negative effects.

[Ken’s] analysis in his article doesn’t stop there though. Not only does he talk more about these JFETs but he goes over the rest of the die too. It’s well worth the read, as is his write-up about the 741 which we’ve also covered.