For [Leigh Oliver], there’s something undeniably appealing about the green on black instrumentation of the 2003 Saab 9-3 Gen2. Perhaps it’s because the Infotainment Control Module 2 (ICM2) screen brings a bit of that classic Matrix vibe to the daily commute. Whatever the reason, it seemed the display deserved better than to be stuck showing the nearly 20 year old stock user interface. Luckily, you can control it via I2C.

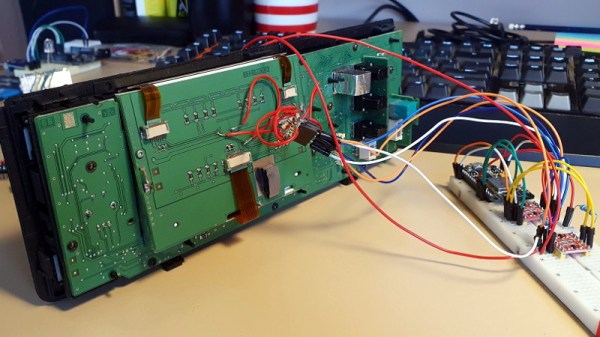

Though as you might expect, that fact wasn’t obvious at first. [Leigh] had to start by taking the ICM2 apart and reverse engineering the display board. With a multimeter and high resolution photographs of both sides of the PCB, all of the traces were mapped out and recreated in KiCAD. This might not have been strictly necessary, but it did serve as good practice for using KiCAD; a worthwhile tip for anyone else looking to build practical experience creating schematics.

With everything mapped out, [Leigh] was able to connect a BusPirate V3 up to the board and pretty quickly determine it was using I2C to control the display. As far as figuring out how to repurpose existing displays goes, this was perhaps the best possible scenario. It even allowed for creating a display library based on

With everything mapped out, [Leigh] was able to connect a BusPirate V3 up to the board and pretty quickly determine it was using I2C to control the display. As far as figuring out how to repurpose existing displays goes, this was perhaps the best possible scenario. It even allowed for creating a display library based on Adafruit_GFX which offers graphical capabilities far beyond what the ICM2 module itself is capable of.

Even with so much progress made, this project is really just getting started. [Leigh] has managed to put some impressive imagery on the black and green Saab display, but the hardware side of things is still being worked on. For example, there’s some hope that an I2C multiplexer would allow the display to easily and quickly be switched between “stock” mode and whatever enhanced version comes about thanks to the new libraries and an ESP8266 hiding behind the dashboard.

If you don’t have a sufficiently vintage Saab to take advantage of this project, don’t worry. Tapping into the OBD port with an OLED display can get you similar results on a wide range of vehicles.