Plenty of gamers around these parts require an expensive PC to play games, often spending thousands of dollars for a gaming machine. Believe it or not, though, there are entire classes of games that don’t require any electronics at all, but that doesn’t mean that they don’t benefit from the addition of some neat gadgets. This Settlers of Catan game uses custom LCD tiles with a built-in custom mesh network.

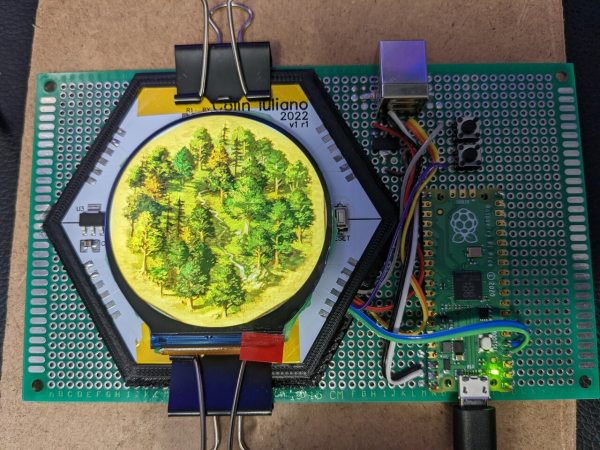

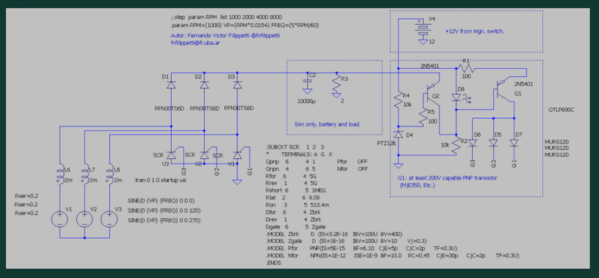

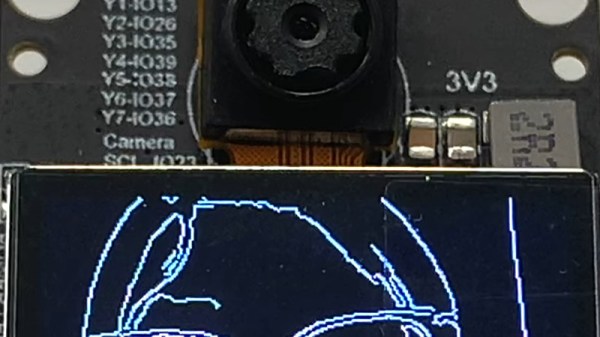

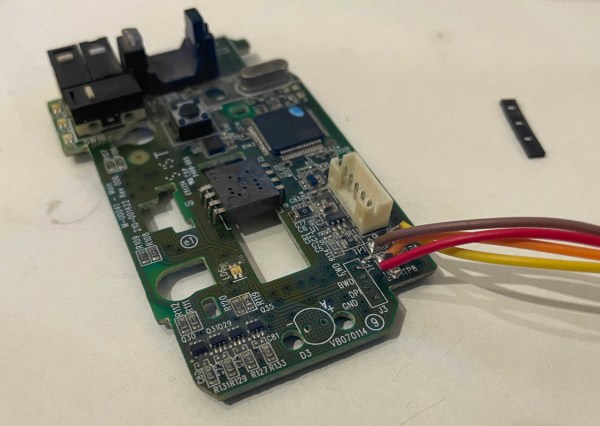

The tiles for the game board themselves are hexagonal and snap together using magnetic pogo pins in order to form a board of any size or shape. The pogo pins also allow communication for a pseudo-mesh network to operate with each tile’s built-in PCB to allow the game board to know exactly which tiles are placed where and to display the correct image on each one. Each tile contains it own RP2040 microcontroller, keeping the overall cost of each tile to a minimum.

For those regularly hosting game night, a project like this could really change the traditionally analog game’s dynamic for the better. It was mostly a project that [Colin Iuliano] built just for fun, and if he ever builds a second one he does plan on some improvements, but we’d say that it looks like a success already. For other Catan-based electronic design inspiration, take a look at this complete and non-modular electronic game board.