The ThinkPad is generally considered the unofficial laptop of hackerdom, so it’s no surprise that we see plenty of projects focused on repairing and modifying these reliable workhorses. But while we usually see folks working on relatively modern incarnations of this iconic line of computers, this project by [Frank Adams] and [Brian Chan] shows that the hacker’s love affair with the ThinkPad stretches back farther than many might realize.

As explained on the project’s Hackaday.io page, the duo have produced an open hardware board that will allow you to take the keyboard and trackpoint from a late ’90s ThinkPad 380ED and use it as a standard USB input device on a modern computer. According to [Frank], the keyboards on these machines are notable for having full-size keys rather than the “chicklet” boards that are so common today.

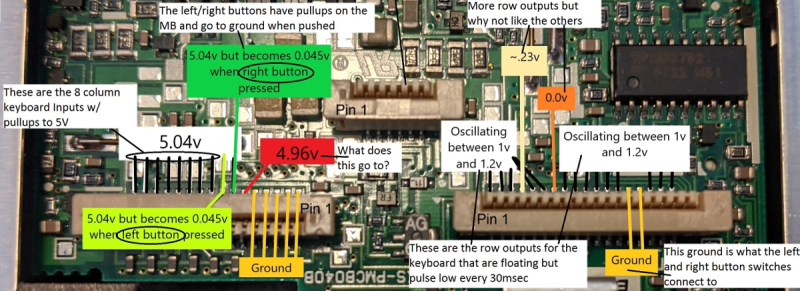

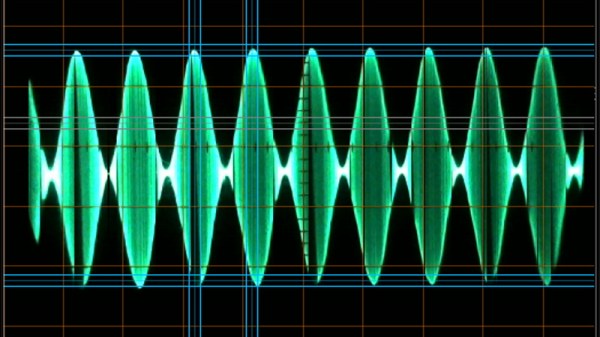

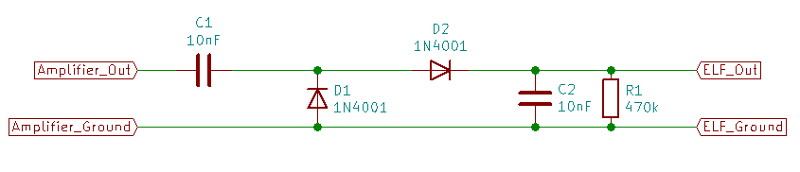

Now you may be wondering why this is significant. After all, we’ve seen plenty of projects that hook up an old keyboard to a USB-equipped microcontroller to get them speaking the lingua franca. Well, the trick here is that the trackpoint on these older ThinkPads actually required additional circuitry on the motherboard to function. The keyboard features three separate FPC connections for the matrix, the trackpoint buttons, and the analog strain gauges in the trackpoint itself.

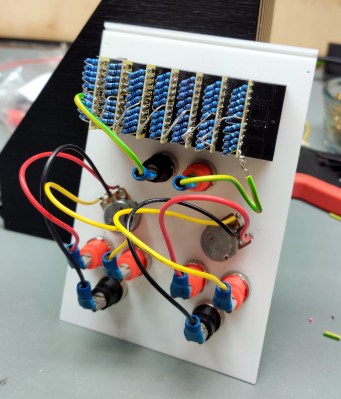

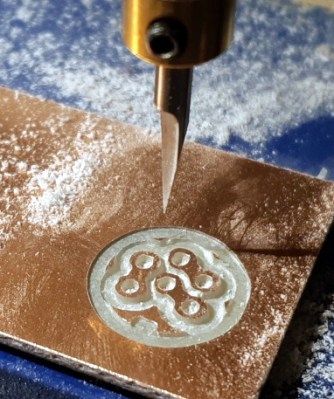

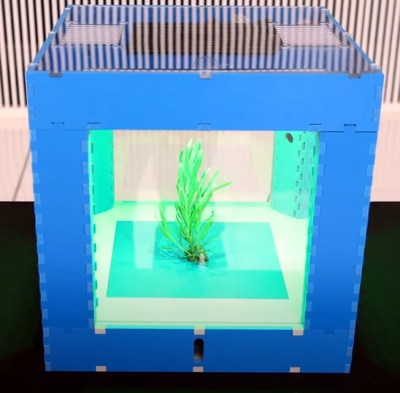

After a considerable amount of reverse engineering, [Frank] and [Brian] have developed a board that uses the Teensy 3.2 to turn this plethora of pins into something useful. In the video after the break, you can see the new composite USB device working perfectly on a modern Windows computer.

It will probably come as little surprise to find that [Frank] is no stranger to hacking ThinkPad keyboards. In 2018 we covered a similar adapter he built for the far more modern T61, which was an absolute cakewalk by comparison.

Continue reading “Breathing New Life Into Old School ThinkPad Keyboards”