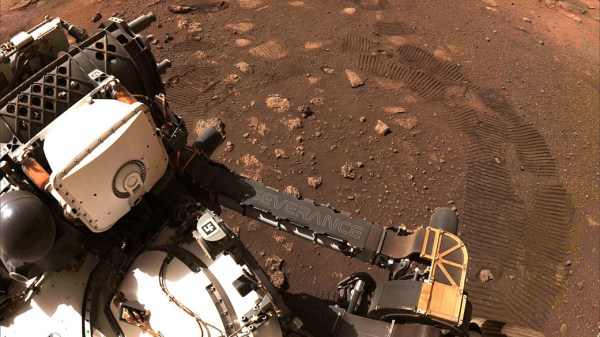

There’s a special kind of anxiety that comes from trying out a robotic project for the first time. No matter the size, complexity, or how much design and planning has gone into it, the first time a creation moves under its own power can put butterflies in anyone’s stomach. So we can imagine that many people at NASA are breathing a sigh of relief now that the Perseverance rover has completed its first successful test drive on Mars.

To be fair, Perseverance was tested here on Earth before launch. However, this is the first drive since the roving scientific platform was packed into a capsule, set on top of a rocket, and flung hundreds of millions of miles (or kilometers, take your pick) to the surface of another planet. As such, and true to NASA form, the operators are taking things slow.

This joyride certainly won’t be setting speed records. The atomic-powered vehicle traveled a total of just 21.3 feet (6.5 meters) in 33 minutes, including forward, reverse, and a 150 degree turn in-between. That’s enough for the mobility team to check out the drive systems and deem the vehicle worthy of excursions that could range 656 feet (200 meters) or more. Perseverance is packed with new technology, including an autonomous navigation system for avoiding hazards without waiting for round-trip communication with Earth, and everything must be tested before being put into full use.

A couple weeks have passed since the world was captivated by actual video of the rover’s entry, descent, and landing, and milestones like this mark the end of that flashy, rocket-powered skycrane period and the beginning of a more settled-in period, where the team works day-to-day in pursuit of the mission’s science goals. The robotic arm and several on-board sensors and experiments have already completed their initial checks. In the coming months, we can look forward to tons of data coming back from the red planet, along with breathtaking pictures of its alien surface and what will hopefully be the first aircraft flown on another world.