When viewed from the far future, the early years of the 21st century will probably be seen as the end of a short era in human technological development. In the beginning of the 20th century, most everything was mechanical. There were certainly some electric devices, but consumer products like gramophone players and “movie” cameras were purely mechanical affairs. You cranked them up, and they ran on springs. Nowadays, almost every bit of consumer gear you buy will be entirely electronic. In between, there was a roughly 50 year period that I’m going to call the Electromechanical Era.

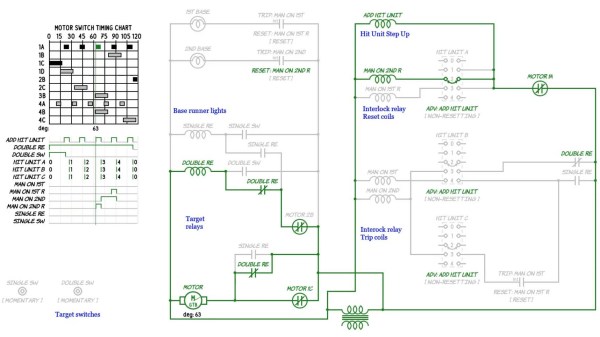

Jenny List’s teardown this week of an old Fuji film movie camera from 1972 captures the middle of this era perfectly. There’s a small PCB and an electric motor, but most of the heavy lifting in the controls was actually put on the shoulders of levers, bearings, and ridiculously clever mechanisms. The electrical and mechanical systems were loosely coupled, with the electrical controlled by the mechanical.

I’m willing to argue the specifics, but I’d preliminarily date the peak of the Electromechanical Era somewhere around 1990. Last year, I had to replace all of the rotted rubber drive belts in a Sony Walkman WM-D6C, a professional portable tape player and recorder produced from 1984-2002.

I’m willing to argue the specifics, but I’d preliminarily date the peak of the Electromechanical Era somewhere around 1990. Last year, I had to replace all of the rotted rubber drive belts in a Sony Walkman WM-D6C, a professional portable tape player and recorder produced from 1984-2002.

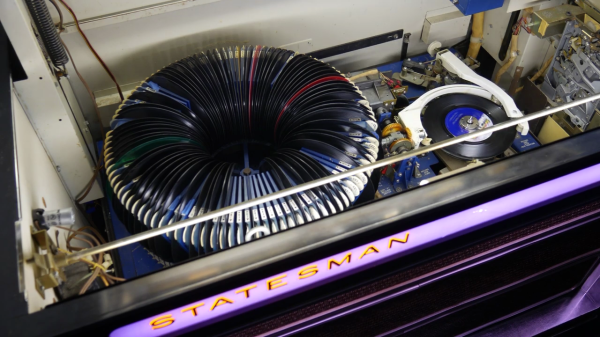

It’s not a simple tape recorder — the motors are electronically regulated to keep ridiculously constant speed for such a small device, and mine has Dolby B and C noise reduction circuitry packed inside along with some decent mic preamps. But still, when you press the fast-forward button, it physically shoves rubber-coated drive wheels out of the way, and sliding pieces of metal make it change modes of operation by making and breaking electrical contacts. Its precision lies as much in the mechanical assemblies and motors as in the electronics. It’s truly half electronic and half mechanical.

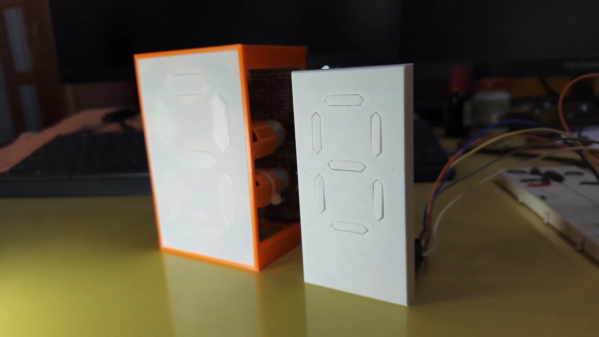

But that era is long over. The coming of the CD player signaled the end, although we didn’t see it at the time. Sure, there is a motor, but all the buttons are electronic, and all the “mechanism” is implemented almost entirely in silicon. The digital camera was possibly the last nail in the Electromechanical Era’s coffin: with no need to handle physical film, the last demand for anything mechanical evaporated. Open up a GoPro if you don’t know what I mean.

While I’ll be happy to never have to replace the drive rubber in a cassette recorder again, it’s with a little sadness that I think on the early iPods with their spinning metal hard drives, and how they gave way to the entirely silicon Zoom H5 recorder that I use now. It has a S/N ratio and quiet pre-amps, no wow or flutter, and a quality that would have been literally unbelievable when I bought the WM-D6C.

Still, if you find yourself in the thrift store, and you’ve never done so before, buy and take apart one of these marvels from a bygone era. A cassette recorder, even a cheap one, hides a wealth of electromechanical design.