It seems like modern roboticists have decided to have a competition to see which group can develop the most terrifying robot ever invented. As of this writing the leading candidate seems to be the robot that can fuel itself by “eating” organic matter. We can only hope that the engineers involved will decide not to flesh that one out completely. Anyway, if we can get past the horrifying and/or uncanny valley-type situations we find ourselves in when looking at these robots, it turns out they have a lot to teach us about the theories behind a lot of complicated electric motors.

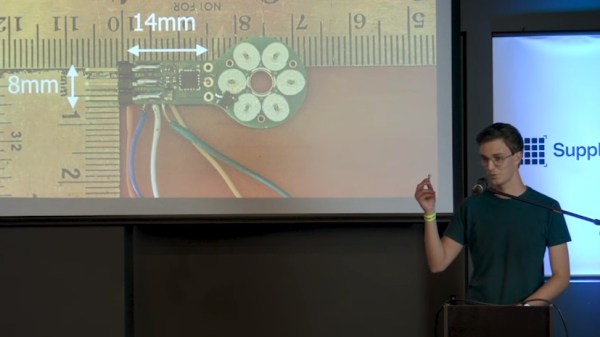

This research paper (gigantic PDF warning) focuses on the construction methods behind MIT’s cheetah robot. It has twelve degrees of freedom and uses a number of exceptionally low-cost modular actuators as motors to control its four legs. Compared to other robots of this type, this helps them jump a major hurdle of cost while still retaining an impressive amount of mobility and control. They were able to integrate a brushless motor, a smart ESC system with feedback, and a planetary gearbox all into the motor itself. That alone is worth the price of admission!

The details on how they did it are well-documented in the 102-page academic document and the source code is available on GitHub if you need a motor like this for any other sort of project, but if you’re here just for the cheetah doing backflips you can also keep up with the build progress at the project’s blog page. We also featured this build earlier in its history as well.