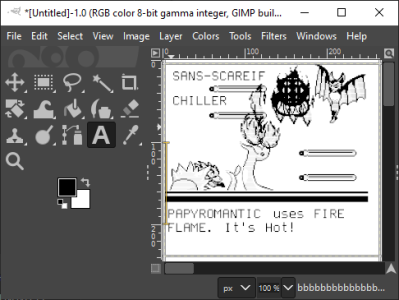

Where’s the last place you’d expect to be able to play a game on your computer? The word processing program? Image editor? How about your text editor? That’s right — you can fight your Fontemons in any program that makes use of fonts, because mad genius [Michael Mulet] has created a game that exists entirely within a single Open Type font file.

[Michael] has harnessed the power of ligatures to create a choose-your-own-adventure-style turn-based game that pokes fun at both Pokemon and various typeface names. You start by choosing between Papyromaniac, Verdanta, and Proggito and face off against enemies like Helvetikhan and Scourier.

This works because there are many ways to draw glyphs on a screen. [Michael] chose Type 2 Charstrings, which is a vector graphics format that Adobe created for PostScript. It can draw pixels with a series of move specifications that tell it to draw up, to the right, and then back down before closing off the pixel with an implicit operator that draws from the starting point to the ending point. [Michael] was able to create two shades of gray by drawing smaller versions of the pixels and making the image by combining white and black pixels.

This works because there are many ways to draw glyphs on a screen. [Michael] chose Type 2 Charstrings, which is a vector graphics format that Adobe created for PostScript. It can draw pixels with a series of move specifications that tell it to draw up, to the right, and then back down before closing off the pixel with an implicit operator that draws from the starting point to the ending point. [Michael] was able to create two shades of gray by drawing smaller versions of the pixels and making the image by combining white and black pixels.

If you just want to play the game, you can either download the .otf file or just try it out in the browser. You’re supposed to use ‘a’ and ‘b’ to make choices that advance the game, but we soon discovered that spamming other keys like ‘v’ and Enter will lead to strange places. If you play it straight, it takes about 20 minutes, but there are enough secrets built in to make it last five times as long. [Michael] was kind enough to create a tutorial for making font-based games, but if you just want to get going, the game engine is open source.

What other fun things can you do on that locked-down work computer? If it has Excel, you can use it to do animation or just kick back and watch a movie.