If you’ve ever tried to cut a piece of acrylic with a tool designed to cut wood or metal, you know that the plastic doesn’t cut in the same way that either of the other materials would. It melts at the cutting location, often gumming up the tool but always releasing a terrible smell that will encourage anyone who has tried this to get the proper plastic cutting tools instead of taking shortcuts. Other tools that heat up plastic also have this problem, as Gizmodo reported recently, and it turns out that the plastic particles aren’t just smelly, they’re toxic.

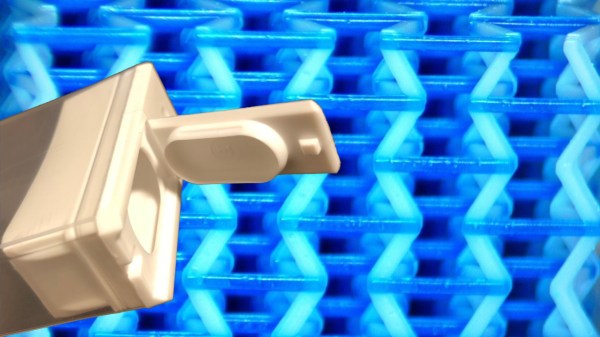

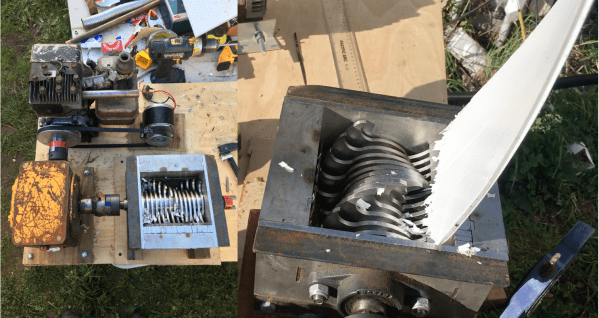

The report released recently in Aerosol Science and Technology (first part and second part) focuses on 3D printers which heat plastic of some form or other in order to make it malleable and form to the specifications of the print. Similar to cutting plastic with the wrong tool, this releases vaporized plastic particles into the air which are incredibly small and can cause health issues when inhaled. They are too small to be seen, and can enter the bloodstream through the lungs. The study found 200 different compounds that were emitted by the printers, some of which are known to be harmful, including several carcinogens. The worst of the emissions seem to be released when the prints are first initiated, but they are continuously released throuhgout the print session as well.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that aerosolized plastic is harmful to breathe, but the sheer magnitude of particles detected in this study is worth taking note of. If you don’t already, it might be good to run your 3D printer in the garage or at least in a room that isn’t used as living space. If that’s not possible, you might want to look at other options to keep your work area safe.

Thanks to [Michael] for the tip!