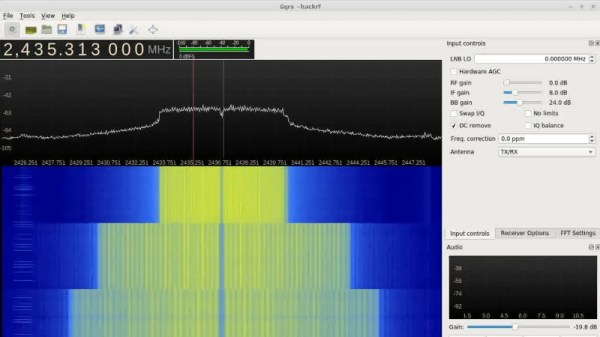

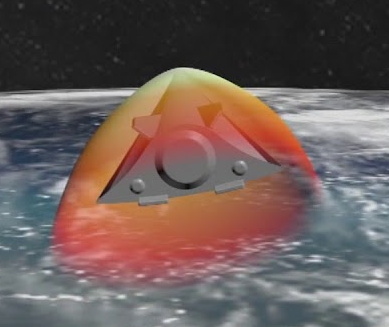

With a highly publicized test firing and pledge by President Vladimir Putin that it will soon be deployed to frontline units, Russia’s Avangard hypersonic weapon has officially gone from a secretive development program to an inevitability. The first weapon of its type to enter into active service, it’s capable of delivering a payload to any spot on the planet at speeds up to Mach 27 while remaining effectively unstoppable by conventional missile defense systems because of its incredible speed and enhanced maneuverability compared to traditional intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs).

In a statement made after the successful test of Avangard, which saw it hit a target approximately 6,000 kilometers (3,700 miles) from the launch site, President Putin made it clear that the evasive nature of the weapon was not to be underestimated: “The Avangard is invulnerable to intercept by any existing and prospective missile defense means of the potential adversary.” The former Soviet KGB agent turned head of state has never been one to shy away from boastful claims, but in this case it’s not just an exaggeration. While the United States and China have been working on their own hypersonic weapons which should be able to meet the capabilities of Avangard when they eventually come online, there’s still no clear deterrent for this type of weapon.

Earlier in the year, commander of U.S. Strategic Command General John Hyten testified to the Senate Armed Services Committee that the threat of retaliation was the best and perhaps only method of keeping the risk of hypersonic weapons in check: “We don’t have any defense that could deny the employment of such a weapon against us, so our response would be our deterrent force.” Essentially, the threat of hypersonic weapons may usher in a new era of “mutually assured destruction” (MAD), the Cold War era doctrine that kept either side from firing the first shot knowing they would sustain the same or greater damage from their adversary.

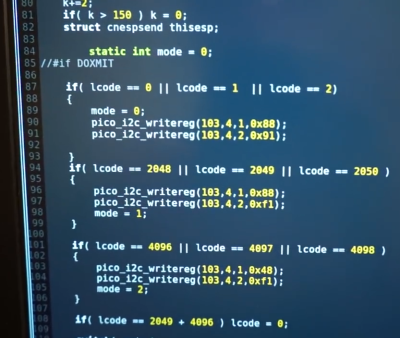

With President Putin claiming Avangard has already entered into serial production and will be deployed as soon as early 2019, the race is on for the United States and China to close the hypersonic gap. But exactly how far away is the rest of the world from developing an operational hypersonic weapon? Perhaps more to the point, what does “hypersonic weapon” really mean?