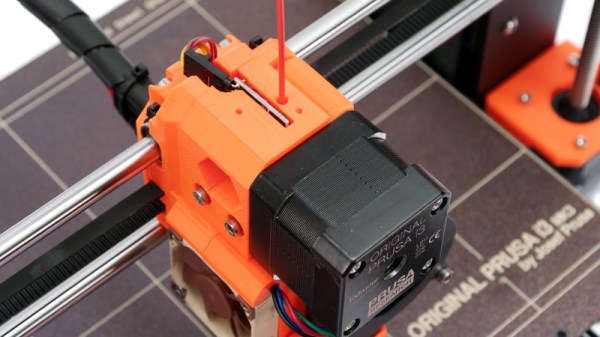

When the Prusa i3 MK3 was released in 2017, it was marketed as being “bloody smart” thanks to the impressive number of sensors that had been packed into the printer. The update wasn’t really about improving print quality over the MK2, but rather to make the machine easier to use and more reliable. There was a system for resuming prints that had stopped during a power outage, a thermometer so the firmware could compensate against thermal drift in the inductive bed sensor, RPM detection on all of the cooling fans, and advanced Trinamic stepper drivers that could detect when the printer had slipped or gotten stuck.

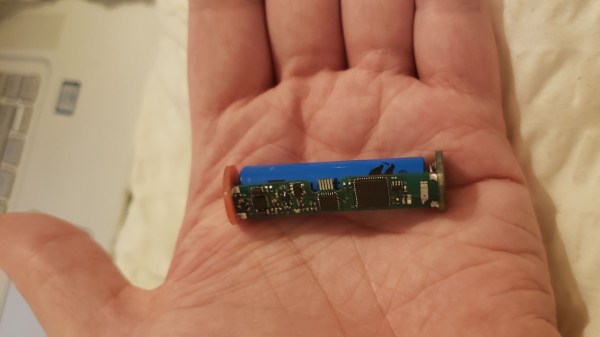

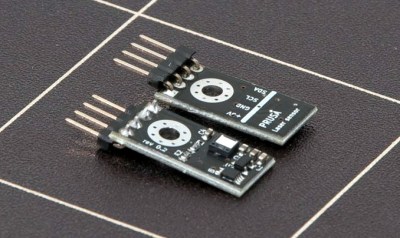

But the most exciting upgrade of all was the new filament sensor. Using an optical encoder similar to what you’d find in a mouse, the Prusa i3 MK3 could detect when filament had been inserted into the extruder. This allowed the firmware to pause the print if the filament had run out, a feature that before this point was largely unheard of on consumer-grade desktop 3D printers. More than that, the optical encoder could also detect whether or not the filament was actually moving through the extruder.

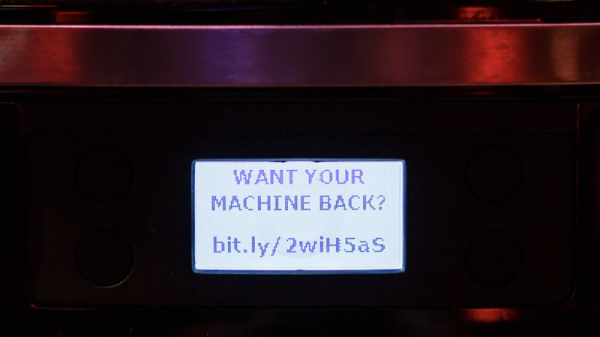

In theory, this meant the MK3 could sense problems such as a jammed extruder or a tangle in the filament path that was keeping the spool from unrolling. Any other consumer 3D printer on the market would simply continue merrily along, not realizing that it wasn’t actually extruding any plastic. But the MK3 would be able to see that the filament had stalled and alert the user. The capabilities of the optical filament sensor represented a minor revolution in desktop 3D printing, and combined with the rest of the instrumentation in the MK3, promised to all but eradicate the heartbreak of failed prints.

Fast forward to February of 2019, and the announcement of the Prusa i3 MK3S. This relatively minor refresh of the printer collected up all the incremental tweaks that had been made during the production of the MK3, and didn’t really add any new features. Though it did delete one: the MK3S removed the optical encoder sensor used in the MK3, and with it the ability to sense filament movement. Users would have to decide if keeping the ability to detect clogs and tangles was worth giving up all of the other improvements offered by the update.

But why? What happened in those three years that made Prusa Research decide to abandon what promised to be a huge usability improvement for their flagship product? The answer is an interesting look at how even the cleverest of engineering solutions don’t always work as expected in the real-world.

Continue reading “The Prusa I3 MK3S And A Tale Of Two Sensors”