How many mundane devices upgrade to IoT because they let you monitor a single data point or a variable? That little nudge over the communication precipice allows you to charge 500% more. Now, if you are as handy as a Hackaday reader, you can throw a lazy afternoon at the problem and get the same effect from a “dumb” appliance. If IoT is as simple as getting a notification when your laundry is dry, or your water is boiling, all you really need is a WiFi device and a push notification, right? Does it need to be more complicated than that? [Gianni] believes it is that simple (machine translation) and has built up an easy-to-implement version on Raspberry Pi, Arduino, and ESP8266.

[Gianni] leverages the aptly named Pushover (a paid app with a 1-week trial period) to convert your bits, bytes, words, or strings to a push notification. This idea is born of the desire for a home security system which doesn’t require constant monitoring but instead alerts you to problems. The minimum requirement you need is for your phone to chime with a notification saying, “Your front window sensor has been tripped.” Now it is time to launch your IP camera app or call someone nearby.

It’s not revolutionary, it may be the “Hello World” of IoT, but that is all some people need. The general idea is the same no matter the framework you want to use. For instance, if you Google Suite account, you can set up a chatroom just for your alert notifications; Google’s quickstart takes about 3 minutes to test it out in Python. The same setup is also available for Slack, and [Tom Nardi] did a guide for doing this with Discord. These tackle the receiving side, but the sending side is really flexible too — that MQTT broker you built could easily be the source of the alerts.

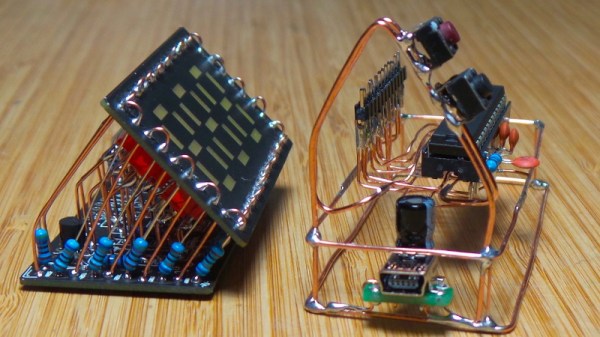

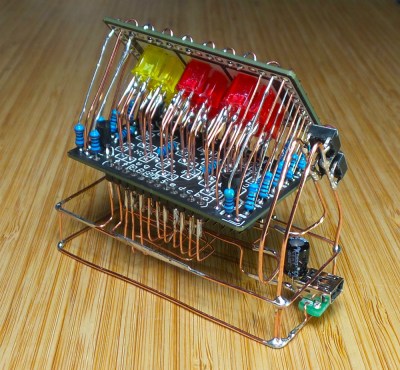

Build a handful of these in a weekend and keep them nearby to step up your next project to IoT status with a couple of solder joints. Maybe it will be a motion sensor for your own security system.