Hoverboards were a popular trend with the youths and in-crowd a few years ago, and now that the fad has largely died out there are plenty of them sitting unused in closets and basements around the world. That only means opportunities to put the parts from these unique transportation devices into other builds. A more practical method of transportation is a bicycle, and this build scavenges most of the parts from a hoverboard to turn a regular bicycle into a zippy ebike.

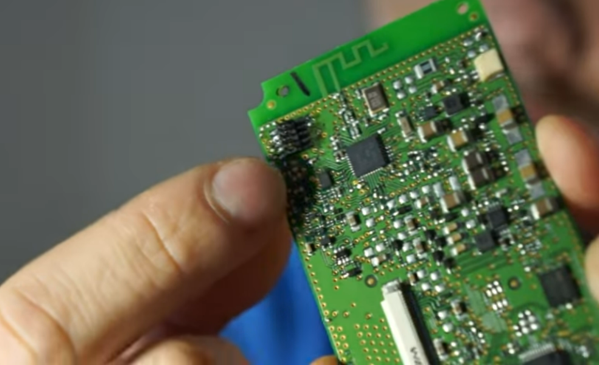

This bike build starts with a mountain bike frame and the parts from the hoverboard are added to it piece by piece. The two motors are mounted to the frame and drive the front chain ring of the bike, allowing it to still take advantage of the bike’s geared drivetrain. Battery packs from two hoverboards were combined into a single battery which give the bike a modest 6-10 km of range depending on use. But the real gem of this build is taking the gyroscopic controller board from the hoverboards and converting it, with the help of an Arduino Due, to an ebike controller.

Eventually a battery pack will be added to give the bike a more comfortable range, but for now we appreciate the ingenuity that it took to adapt the controller from the hoverboard into an ebike controller complete with throttle and pedal assist. For other household objects turned into ebikes, be sure to check out one of our favorites based on a washing machine motor: the Spin Cycle.